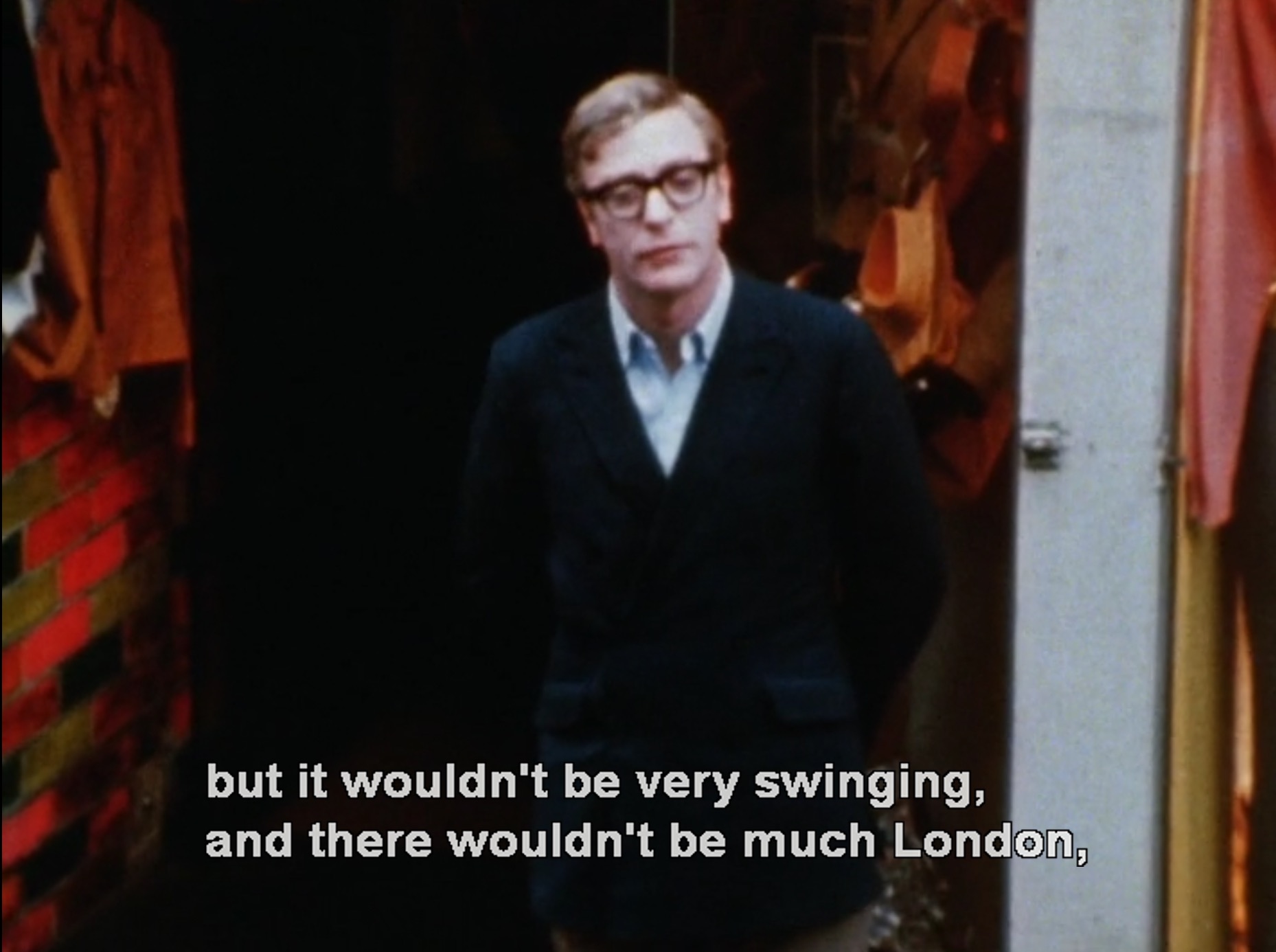

In 1969, a great film on the Battle of Britain was produced in England. Among the famous actors starring in that movie was Michael Caine, who played the role of an RAF Wing commander. In an interview, he explained why the battle of Britain was so important: without the heroic fight of the Few, the younger generation wouldn't have enjoyed the same freedom. The sacrifices made in the summer of 1940 were a prerequisite to the Swinging London of the Sixties.

Part One: Britain in WW2

2 | The Battle of Britain

Visit the Royal Air Force museum's exhibit on the Battle of Britain.

Visit the Royal Air Force museum's exhibit on the Battle of Britain.

TG4/5 on 30 September 2022; TG2 on 5 October.

➣ Some complements about the memories of the Battle of Britain (TG2, partially annotated with the TG4/5).

New in the “howto” page : some hints to comment on Churchill's speech about “The Few” and the original broadcast.

Available subjects to be prepared at home and to be presented in class beginning on 30 September (TG4/5) or 5 October (TG2) Those subjects will remain possible for the next three weeks (until October 14 in TG4/5, October 16 in TG2). You can choose any of them:

- On the Battle of Britain: Hitler's instructions, the narrative of Dennis Newton, an ace fighter pilot of the RAF, and a photo of a German bomber over London.

- On the Battle of Britain: text by the English ace pilot Peter Townsend and picture of a crashed Messerschmitt.

- On the Battle of Britain: Churchill's famous speech “Never was so much owed by so many to so few” and a photo of Churchill visiting London after a German raid..

This is our last class on the battle of Britain. Next week: the Blitz and the home front, with new subjects.

What the “many” owe to the “Few”.

➣ Read: Richard Overy, born in 1947, is the leading historian on the Battle of Britain. In his book, published in 2000, The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality, he emphasises the importance of the battle for the British:

« The Battle of Britain mattered above all to the British people, who were saved the fate that overtook the rest of Europe. The result was one of the key moral moments of the war, when the uncertainties and divisions of the summer gave way to a greater sense of purpose and a more united people. This was a necessary battle, as Stalingrad was for the eastern front. In June Kenneth Clark reported to the Ministry of Information the effects of a recent morale campaign. He confessed that the campaign had not been a success: ‘people do not know what to do… difficulty arose in satisfying the people that the war could be won’. By November the mood was less desperate. A Gallup Poll showed 80 per cent of respondents confident that Britain would win in the end. Ministry informers reported a widespread desire to end the propaganda ‘Britain can take it’ and to substitute the slogan ‘Britain can give it!’

Even civilians enjoyed the sense that they, too, could contribute directly to the war effort through their own sacrifices and endeavours. There emerged an evident mood of exhilaration when the population found itself fighting at last after months of inactivity. Men flocked in thousands to join the Local Defence Volunteers, though they were poorly organized and scarcely armed by the time invasion was likely: many would have been treated, as the German side made clear at the time, as irregular militia, subject to summary execution. The Battle of Britain and the Blitz that followed contributed to the growing sense that this was a people’s war. There is more than a touch of irony that the battle was actually won by a tiny military elite, and at the cost of only 443 pilots in four months. The heroic defences on the eastern front, of Moscow and Sevastopol and Stalingrad, cost the defender, soldier and civilian, millions of war dead. The efficiency of Britain’s defensive effort in 1940 was one of its most remarkable features. The ‘few’ did indeed save the many from a terrible ordeal. »

TG4/5 on 23 September 2022; TG2 on 28 September.

Squadron leader Peter Townsend of the RAF exits his Hawker Hurricane fighter. England, July 1940. Townsend was an ace pilot and – in Churchill's own words – one of the “few”, who won the battle of Britain and to whom the British people owed their freedom. Though not as advanced as the Spitfire, the Hurricane was a sturdy, reliable fighter which matched its German counterpart, the Messerschmitt Me-109, except for speed and climbing rate.

Those are TG4/5's notes. TG2's can be downloaded here.

The context of the battle of Britain.

- France asked for a ceasefire on 17 June 1940 : Britain was now alone against Hitler.

- Hitler was seeking peace: he was now the master of continental western Europe.

- But Churchill was determined to go on fighting. Otherwise, Hitler, who was triumphant, would have been a deadly threat for the British Empire. That’s why the battle of Britain (BoB) happened.

1. The order of battle: comparing military power on either side.

- The Germans had a clear superiority in numbers;

- Their morale was high: they were deemed invicible;

- The threat of an invasion (of England by the Germans) was real.

- The RAF had the best air defence system worldwide (the most advanced):

- the RADAR network (RAdio Detection And Ranging);

- state of the art fighter aircraft, like the Spitfire. Compared to the German Messerschmitt 109, the Spitfire was a bit slower, but more maneuverable (swifter).

- during the BoB, the British knew that, if shot down, their airmen could bail out, be rescued, and fight another day;

- conversely, a German aircraft shot down was a total loss: the pilot would be killed or captured.

- when fighting above England, the Germans were quickly short of fuel. This meant that the fighters had to leave the bombers on their own.

2. Hitler’s strategic mistake.

- at the beginning, Hitler attacked the convoys in the Channel, to deplete the Royal Navy and the flow of supplies to the UK (July 1940);

- then, he attacked the airfields, which inflicted severe losses to the RAF Fighter Command. That strategy was very dangerous for the British (August 1940);

- at that point, Churchill launched raids on German cities to provoke Hitler who, immediately, retaliated on British cities, first of all London. Churchill said “London can take it!” (September 1940, the beginning of the Blitz).

Therefore, Hitler never achieved air mastery over England. The invasion (“Sea Lion”) was postponed, later cancelled.

Germany, however, was still occupying the continent. Hitler was far from defeated.

➣ Read: Sebastian Haffner was a German publicist and writer and an opponent to Hitler. In that excerpt of his book, The meaning of Hitler (1978), he explains the flaws of Hitler's strategy towards Britain.

Hitler intended that Britain should play the part of an ally or at least of a benevolent neutral. He had made no preparations for an invasion of England or for a naval war of blockade against Britain on the high seas. He shied away from an improvised invasion, probably rightly in view of British superiority on the sea and in the air. Terror bombing proved a poor means of making Britain grow weary of the war; if anything it was counterproductive. Thus, from the summer of 1940, Hitler had the undecided, unsought-for war with Britain hanging round his neck, a first indication that his policy of 1938/39 had been mistaken. [...]

He was not interested in the fact that a continental European peace, which was then due, would have been bound to starve Britain’s resolution. Indeed, he was not really interested in the war against Britain at all: it had not been part of the plan, and it did not fit into Hitler’s picture of the world. That America was drawing menacingly closer behind Britain, Hitler for a long time refused to take seriously. He relied on America’s backwardness in armaments, on the domestic disunity between interventionists and isolationists, and, at the worst, on America being diverted by Japan. In his own programme of action America did not figure.

TG4/5 on 16 September 2022; TG2 on 21 September.

➣ How did Britain withstand the German air offensive in the summer of 1940?

WAAF (Women's Auxiliary Air Force) plotters would plot incoming enemy aircraft detected by the RADAR stations on a map. Appropriate timing was essential because air refuelling did not exist. Fighters had only a limited range. They could remain airborne for 90 minutes only, so that they had to be scrambled just in time to intercept the German bombers. The mobilisation of women exemplifies the situation of total war: other women were mobilised in the factories, in the agriculture, or as doctors and nurses. Photo: Imperial War Museum.

❑ Subject: “The threat of a German invasion” ; Churchill's speech on 11 September 1940 and a letter of Maria Blewitt, a WAAF, on the same day.

➣ See the annotated version of the subject (TG2).

➣ Watch: Andrew Marr's BBC documentary Britannia at bay, part 6 of his series on The making of modern Britain (Excerpts used in class).

➣ Read: Adam Tooze is a British historian. In his book, The wages of destruction, the making and breaking of the nazi economy (2006), he gives an in-depth account of the German war effort. Among other conclusions, he insists that the battle of Britain exposed the shortcomings of the German aircraft industry: the Luftwaffe did not have the capabilities for the strategic air war envisioned by Göring (Pages 447-448).

If there was one thing that the Battle of

Britain had made clear, it was the shortcomings of the Luftwaffe's

development programme. The aircraft that were already in production

had proved themselves unable to achieve a decisive victory over the

Royal Air Force. The Junkers 88 medium bomber was far from being

the war-winning universal combat aircraft that had been sold to Goering

in 1938. A battlefield report commissioned from squadrons stationed

on the Channel coast recorded that the aircrew were 'not afraid of the

enemy, but were afraid of the Junker 88'. It was slow, it lacked effective

defensive armament and for strategic bombing its payload was hopelessly

inadequate. With upgraded engines, both the older-generation

medium bombers, the He 111 and the Do 17, proved capable of outperforming

the Ju 88, their designated successor. [...] To call into question the qualities of

the Ju 88 was to call into question the entire basis of Luftwaffe development

over the previous three years, as well as hundreds of millions of

Reichsmarks of investment.

The Luftwaffe's other main aircraft, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 was an

excellent short-range fighter-interceptor, but it had been in operation

since the Spanish Civil War and it could be kept competitive only by

repeated upgrading. [...] And it was clear that in the foreseeable future it

too would need to be replaced. The Focke Wulf FW 190, which was

nearing combat readiness in early 1941, offered a substantial advance

in performance. But Focke Wulf's management lacked the political clout

of Willy Messerschmitt, and the BMW radial engine around which the

plane had been designed was proving extremely troublesome. Messerschmitt's

other mainstay, the Me 110 heavy fighter was one of the real

casualties of the Battle of Britain. Intended as a long-range escort for

Germany's bombers, it had been hopelessly outclassed by the fighters of the

RAF.

➣ Also look at 9 iconic aircraft from the battle of Britain at the Imperial War Museum.

Eric Lock (here on the left), nicknamed “Sawn-off Lockie” because he wasn't tall, was a popular English fighter ace. He shot down 21 German aircraft, 15 of which in only 19 days. He died in a mission over France on 3 August 1941. In the background, a Spitfire (Photo: Imperial War Museum).

➣ Read: Ten inspiring stories of bravery during the battle of Britain at the IWM (Imperial War Museum),

and 8 things you need to know about the Battle of Britain.